Do you lock up or take care of someone when you take someone into custody? How frustrating that, according to general rules, I have to write “he” in order to present to the public the image of both a man and a woman. What are the patterns of thinking reaffirmed by this? How will the woman fit into the public eye’s (not) image of her?

These questions fuel it Proof of custodythe second collection for Iduna Paalman (1991), who debuted as a poet in 2019 with Get the growl out of the dog. In her new collection of poems, women’s flawed historiography is not only criticized, but history is also rewritten. An impressive parade is given a second chance, from women condemned as witches, women who discovered comets and made inventions that barely appear in the history books, to women who still struggle with their self-image to this day.

executed witch

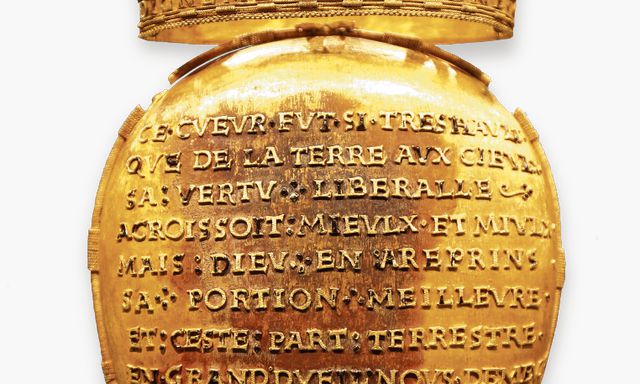

Women do not come to life without effort. There is a lot that needs to be explained and corrected. The poems are sometimes austere, as in “Enforcement,” which talks about a murder on behalf of the justice system.

The beheading of Anna Goldie is not a fancy event, nor is it a fancy breakfast

A milk feast is a miscarriage of justice, though that number is only over two hundred

Years later it becomes known, and admitting a mistake always takes longer

Then he commits the error, no matter how long the error persists

Anna Goldie (1734-1782) I have to search. She turns out to be the last person to be executed as a witch in Europe. Did I not care about it, or did it not appear in history lessons at school? Goldie’s introduction is followed by a more sonorous passage in which the executioner appears to speak for himself. Or does this sound like Paalman himself? As is so often the case in the group, “I” can be read as a vehicle that all women (and men) can identify with.

I’ve been sitting on a gold mine for years because I live so clearly, and my breath is still there

Within the usual bites and hiccups in tune to my request for help

Mine turns out to be a manhole cover, the lid turns out to be a roof, and lobsters stink under it

The organizers slept, they got up early

But the artists are still there

Also read a review of the first set by Iduna Paalman: Get the growl out of the dog He convinces with his voice

I think the hole is a picture of the history in which women disappeared, which is brewing under the manhole cover. Or is it a system of passages expanding into the consciousness of the first form? The surreal, image-rich content does not reveal itself easily. Tone looms through the voice, but it’s also from someone in control. It sometimes keeps me at bay, then tempts me to sway: I sit, slightly disoriented, on the edge of my seat while I read.

pleasure

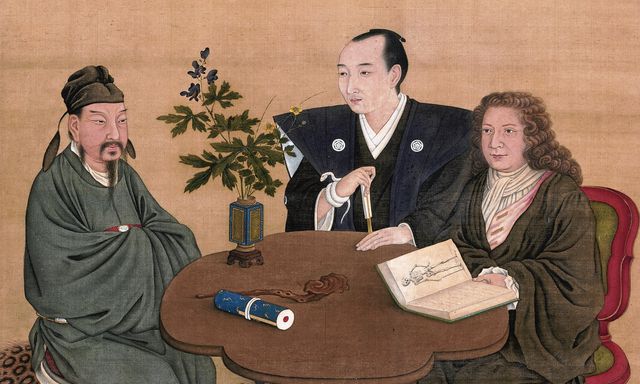

This experience is remarkably similar to the way a woman would take in an ordinary history book. She wants to participate, but she hardly recognizes herself in anything. General history does not relate to her and keeps her at bay. It is poignant and poignant that Paalman’s poems reflect, not only in what they describe but also in what they evoke, what it means to have behind not one zero, but at least two millennia of patriarchy.

What this looks like in practice is illustrated, for example, by “Proof of Acceptance”, where women struggle with how satisfaction Should be, to fit in. Exactly where it is and what it is trying to adapt to remains unclear, but it could be the average meeting or workplace.

Even though you are wearing a nice cream blouse and serving someone

Scold, your figure is still very flat, and you become very good

Understandably, you made the bottle of wine crucial

But he still obediently stands there

Also read Anne Koala’s Poetry Collection review: Women play a starring role in this date

So far the situation is clear. It becomes more ambiguous in the following lines, which switch between martial prowess and manual dexterity. If you want to get in, you have to use yourself: “Demonstration can hang / But it can also be design, you have to think about it if you really / Want to go through with this.” Speech seems to be an inner voice shaped by the audience’s gaze. Then mystery gives way and Paalman appears to slam his fist on the table: though all the books are about you, unfortunately you can gain nothing from them.

In addition to confinement or care, “custody” can also refer to where Create an alternate date. The collection as a whole, full of testimonies from women who are still given the right and space to testify about their lives, can be “evidence” of this.

Just like the ambiguity of the concept of “detention,” Paalman examines the concept of “barrier” to discuss issues such as gun possession and contraceptives. What you protect yourself with and feel comfortable with can also be harmful, is the uncomfortable message.

Contraceptive

How is it possible that I didn’t love him sooner Mary Gertrude Halton I heard, who designed the silk cocoon as a contraceptive? Is it now in the history books used in school? The Barrier Means cycle begins with four poems that would be sonnets if the last two stanzas were not four or two lines long, but both three lines. A clear interjection with which Balmain does not completely avoid tradition, but gives it its own form.

breathes Proof of custody It’s when a piece of music doesn’t have to hold history for a while, it doesn’t have to represent anyone, it doesn’t have to get anything right. Though the airiness is treacherous—after all, Paalman has to fight for that freedom with a brave bundle—it does produce wonderfully tender moments, as in “This Goes To Everyone”:

No, I don’t have much to hide

Actually nothing

Actually, I have nothing to hide

In fact, I really have nothing to hide

A big one comes out

I’m very present and that’s a good thing because if I’m not there

I don’t know

Also read the review of “The Universal History of Science”: You know Newton and Darwin, but why don’t you know Kwasi and Saha?

Brilliant is the concluding poem in which two astronomers, Maria and Maria, drink on a balcony and look up at the night sky. They mirror each other. Both Maria Margareta Kirch (1670-1720) if Mary Mitchell (1818-1889) Discover a comet.

They look up at the night sky as the light gets bigger

And round, look they say laughing

How dangerous is it, how pioneering is it

They drink and then say nothing

Paman made the two women look at the sky together as if it were their lives, which could mean little in terms of the universe. They have to laugh about that. Here the content of the group is called into question: Does the desire to be “dangerous” and “pioneering”, as well as the desire to rewrite history, mean enough? There is no answer, but a desperate but meaningful silence: silence is better than silence.

A version of this article also appeared in the January 27, 2023 Journal